This is an approach to preparing an application for leave to appeal.

An appeal is a request to a higher court to rehear and review the court below’s decision (‘the original decision’).

An appeal can happen from the subordinate courts, comprised of the magistrates and sessions courts, to the High Court (Scenario 1) and subsequently from the High Court to the Court of Appeal (Scenario 2). It can also happen from the High Court to the Court of Appeal (Scenario 3) and subsequently the Court of Appeal to the Federal Court (Scenario 4).

For civil matters, there is only one right of appeal. Suppose a litigant wants to appeal in a Scenario 2 or 4 situation. In those cases, the appellant (person appealing) requires the higher court’s leave to appeal i.e., ‘permission to appeal’, before he may file his appeal.

For criminal matters, the situation is different. There are two rights of appeal: the appeal against the original decision and the appeal against the appeal. There is no need to obtain the higher court’s permission to appeal against the appeal. It is as of right.

This guide is only concerned with civil matters and only for Scenarios 2 and 4 i.e., applying for leave to appeal to a higher court. I wrote earlier about how to approach appeals for Scenarios 1 and 3.

Scenario 2 is applying for leave to appeal from the Court of Appeal (CA). Scenario 4 is applying for leave to appeal from the Federal Court (FC). Different legal tests apply even though they are both about obtaining leave to appeal. This guide considers the test for leave for Scenario 2 and then Scenario 4.

Applying for leave at the Court of Appeal

Firstly, it should be understood that not all matters are appealable.

Section 68(1) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (‘CJA64’) prohibits appeals to the CA for a limited class of matters. For example, there is an absolute prohibition against appealing a consent judgment (section 68(1)(b) CJA64), a decision which the law says the High Court’s decision is final (section 68(1)(d) CJA64), or against a High Court’s decision dismissing an application for summary judgment (section 68(1)e CJA64), or to strike out a claim (section 68(1)(f) CJA64), or allowing a judgment in default to be set aside (section 68(1)(g) CJA64).

Secondly, some matters are not appealable but they can be appealed with the court’s leave or permission.

For example, there is a conditional prohibition against an appeal where the value of the subject matter of the claim is less than RM 250,000 (section 68(1)(a)) or the appeal is only about the costs awarded by the High Court (section 68(1)(c)). Conditional prohibition because if we can appeal these matters if we obtain leave the Court of Appeal’s leave.

Where the value of the claim is concerned, the determining factor is the amount claimed in the statement of claim, not the amount determined by the court: Yai Yen Hon v Teng Ah Kok & Sim Huat Sdn Bhd & Anor [1997] 2 CLJ 68, FC.

Thirdly, if an appeal requires the court’s leave to appeal and the appellant fails to apply for leave before filing its appeal, the appeal is a nullity. The court will strike out the appeal: see Yai Yen Hon v Teng Ah Kok & Sim Huat Sdn Bhd & Anor [1997] 2 CLJ 68, FC.

To apply for CA leave to appeal, we need to understand and appreciate the threshold to meet for the CA to give leave. There is a seeming ambiguity among the CA decisions because they use different terminologies and do not set clear standards. Three CA decisions consider the threshold for leave to appeal under section 68(1)(a) CJA64.

The first is Yai Yen Hon v Teng Ah Kok & Sim Huat Sdn Bhd & Anor [1997] 2 CLJ 68. Here, Abu Mansor Ali JCA held the applicable test was the one laid down in the High Court decision of Pang Hon Chin v Nahar Singh [1986] 2 MLJ 145 by Edgar Joseph Jr J, which decided that ‘leave can only be given “where the applicant can demonstrate a prima facie case of error.” This is the ‘Prima facie error’ test.

The second is Golden Hope Plantations (Peninsular) Sdn Bhd (Ladang Sungei Senarut) v Sarawathy Kathan [2009] 3 CLJ 335. Low Hop Bing JCA gave leave to appeal for a matter where the value of the appeal was RM 250.08 because an appeal against ‘the decision of the High Court was immensely important and had far-reaching consequences.’ This is the ‘Immensely Important’ test.

The third is the most recent of the trilogy of cases, Harcharan Singh Sohan Singh v Ranjit Kaur S Gean Singh [2010] 3 CLJ 29. Tengku Baharudin Shah JCA held that the applicant must show good and compelling reasons for its exercise. This is the ‘Good and Cogent Reasons’ test.

The ambiguity arises because section 68(1)(a) and (c) CJA64 are not clear about what the applicable test is. It is therefore the CA’s task to work out what that test is. I believe the generally applicable test is the Good and Cogent Reasons as stated in Harcharan Singh Sohan Singh and should be decided on a case-to-case basis. It is properly ambiguous in its scope.

The Prima Facie Error test in United Oriental Assurance Sdn Bhd is or should not be the only applicable test. A Prima Facie Error is a Good and Cogent Reason to give leave to appeal. A Prima Facie Error should be treated as a ground, not a standard. The same goes for the Immensely Important test in Golden Hope Plantations (Peninsular) Sdn Bhd. That an issue of law is immensely important and has far-reaching consequences is a Good and Cogent Reason to give leave to appeal, but that should not be treated as a standard.

That means to obtain leave to appeal, we must show Good and Cogent Reasons. That is a bit like unfairness – we know it when we see or feel it. What is clear is that if we can show a prima facie error of law or that the issue of law is important and has wide applicability, the chances of obtaining leave are higher. But those are not the only situations which demonstrate good and cogent reasons for leave to appeal.

Since the test for leave to appeal is ambiguous and open, my suggestion is to read as many decisions as you can (there won’t be many) where the court explains why it gave leave to appeal for that particular matter to get a sense of how the court approaches it. It boils down to explaining to the court why the CA should hear the appeal – What is in it for the parties or the development of the law and justice?

Applying for leave at the Federal Court

Firstly, it must be understood the Federal Court only hears appeals that meet the threshold of section 96(a) and (b) CJA64. I will deal with the latter first because it is straightforward compared to the former.

Under section 96(b) CJA64, the FC must give leave to appeal from ‘any decision as to the effect of any provision of the Constitution including the validity of any written law relating to any such provision.’ That means if the CA decision appealed relates to the interpretation of a Federal Constitution provision, which includes a challenge on the validity of any law, leave to appeal must and will be given. In short, so long as the decision involves constitutional interpretation, permission to appeal must be given as a matter of course.

That makes sense because the Federal Court is the highest authority on matters relating to the Federal Constitution: see Article 128(1) and (2) and Article 130, Federal Constitution. It is under a duty to resolve matters relating to the Federal Constitution.

Section 96(a) CJA64 is the provision most of the cases apply under for leave to appeal. Most decisions decided in the Court of Appeal lack a constitutional dimension. If the Federal Constitution is not engaged, the conditions in section 96(a) CJA64 have to be satisfied before the FC gives leave to appeal.

The leading case about section 96(a) is the FC decision of Terengganu Forest Products Sdn Bhd v Cosco Container Lines Co Ltd & Anor & Other Applications [2011] 1 CLJ 51. For those who want to appreciate the evolution of section 96(a) CJA64 test, I recommend first reading Datuk Syed Kechik Syed Mohamed & Anor v The Board of Trustees of the Sabah Foundation & Ors [1999] 1 CLJ 325 and then Joceline Tan Poh Choo & Ors v V Muthusamy [2009] 1 CLJ 650, then the current leading case.

Terengganu Forest Products Sdn Bhd clarified that to obtain leave to appeal, a matter must fall under one or both categories under section 96(a) CJA64.

The first category is whether the matter or question of law raises a question of general principle not previously decided by the FC. This is known as the Novely Limb. The FC will only give leave or permission for questions of law that it has not decided before.

The second category is whether further argument about the question of law or matter raised is important and a FC decision would be to public advantage. This is known as the Public Importance Limb. The FC will only give leave or permission for questions of law which are important and beneficial to the public.

The first and second categories are separate and independent. So an application can be made on just the Novelty Limb or just the Public Importance Limb. The applicant only needs to succeed under one limb. However, the courts recognize that the questions of law or matters may fall into both categories. That is uncommon. More likely, we will argue those limbs in the alternative instead of simultaneously.

An appeal to the FC must fulfil either or both of these two categories.

If it doesn’t, leave or permission will not be given by the FC to appeal. It is important to appreciate that even though the Court of Appeal committed a serious or flagrant error of law or facts, until and unless a matter or question of law fulfils the Novelty Limb or the Public Importance Limb, the FC will not give permission to appeal.

It can be inferred from section 96(a) CJA64 that the FC is not interested in justice or correcting wrongs. The FC is more concerned with the exposition of the law i.e., an issue that was not decided previously, or where the law benefits from further argument and an FC decision, or where a constitutional provision requires consideration. That justice is done or wrongs corrected is of secondary importance. That explains the basis of the quote below:

Section 96(a) does not mention achieving justice or to correct injustice or to correct a grave error of law or facts as grounds for granting leave to appeal. Every applicant would inevitably claim he has suffered injustice but the allegations of injustice by itself should not be a sufficient reason for leave to be granted. But once leave is granted on any one or more grounds discussed in this judgment this court can of course hear any allegation of injustice.

per Tun Zaki Tun Azmi, Terengganu Forest Products Sdn Bhd v Cosco Container Lines Co Ltd & Anor & Other Applications [2011] 1 CLJ 51, paragraph [31]

Once we get leave or permission to appeal only then can we raise the issue of the Court of Appeal’s injustice or errors. Showing the Court of Appeal was plainly wrong is insufficient to satisfy the requirement under section 96(a) CJA64. I wonder at the policy thinking is behind this. It privileges convenience prevails over ensuring justice.

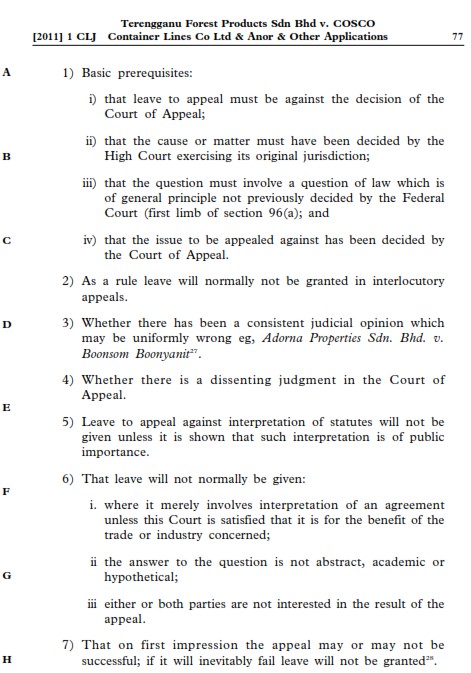

The FC in Terengganu Forest Products Sdn Bhd set out a useful guideline of matters to be mindful of when preparing for an FC leave application. They are helpful and are reproduced below.

Those are the guidelines on the test to meet in applying for leave to the FC and CA culled from case law and my experience.

Whether the FC and CA follow their own rules, guidelines and laws in granting leave to appeal is an entirely separate matter not within the scope of this guide.

Related Posts

- The Importance of Not Using Metaphors to Describe Symptoms

Once in my teens, I went to see my usual doctor, a general practitioner, in…

- Preparing Statements of Agreed Facts and Statements of Issues to be Tried

In the preparation of trials, the court orders parties, as a matter of course, to…

- Mass Calls to the Bar

My experience of calls to the Bar is one borne from moving calls mostly at…

- The Death Penalty

Are you for or against the death penalty? I have never liked that question because…

- My ability to type fast | From the Atelier

I followed Zee Tan's work on Facebook before I got around to approaching him for…

1 thought on “A short guide to applying for leave to appeal”