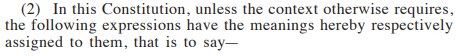

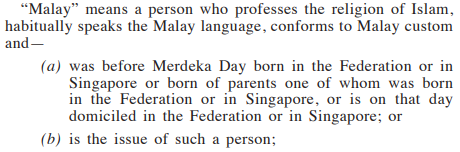

According to the definition provision of the Malaysian Federal Constitution (FC), Article 160, a person who fulfils four conditions is considered a Malay:

- Professes the religion of Islam (Religion)

- Habitually speaks the Malay language (Language)

- Conforms to Malay custom (Custom)

- Either born, born of parents, one of whom must be born or domiciled in Malaysia, or the child of those parents (Malaysian Parent)

I have bracketed the categories and will use them as shorthand for those conditions. Other races are not defined. Only what constitutes a Malay. Since knowing about this provision, I have always wondered whether having a fossilized definition of a Malay over the long term is healthy.

It is obvious from the FC definition that Malayness is not a matter of biology. It is a matter of what you believe, what language you use, what Malay customs you observe, and you are an issue of a Malaysian parent. A Malay is about how you behave and what you believe than your biological composition.

So long as a person fulfils those four conditions, they are Malay. You do not need to have a father or mother who is biologically Malay.

That means any person can be a Malay. You can start as a Chinese, Indian, English, Thai, or a member of the Piraha tribe from the Amazon in South America or the Yupik tribe from Alaska. So long as you fulfil those conditions, you are Malay.

For example, I knew of a non-Malay lady who claimed she was Muslim, spoke Malay habitually, practised Malay customs and was a child of a Malaysian parent. She came to see me in my previous firm to file a declaration that she was a Malay pursuant to the FC. I did not take up her matter because of fees – she wanted me to do it for a pittance. I refused.

However, I heard she eventually found a lawyer to obtain the orders she sought, which suggests it is possible to become a Malay. I don’t see why not. It is not a biological matter.

It is an evidential matter. Can she prove she speaks Malay habitually? She can bring witnesses to testify to this. Can she prove she is Muslim and a Malaysian citizen? She can show her identity card and her muallaf card (Muslim convert card). Can she prove she observes Malay customs? She can bring a Malay cultural expert to testify or write a report about her observance with them.

I call these sorts the ‘constitutional Malay’. She could now reap all the benefits of being a Bumiputera, just like a ‘pure Malay’, i.e., those born of a Malay couple. The FC does not distinguish an ‘original Malay’ and a court-declared one.

But here is the funny thing: even though the FC identifies Malays by their beliefs, customs, and daily speech, the government classifies us as Malays by marriage and biology, irrespective of our beliefs, observance of customs or daily speech. This puts some of us in a strange situation.

Me, for example.

I am Malay because my father is Malay. My mother is Chinese. I am actually Malay/Chinese. I have extended families on both sides. What is the weightage of each? Am I more Malay or Chinese? I don’t know. Frankly, I don’t care. My race has always been a matter of irrelevance for me.

That is because my parents raised me in a way that rendered the issue of race irrelevant. They made sure I was, more often than not, in a racially diverse environment. I have always unconsciously perpetually made sure I had close Malay, Chinese and Indian friends and continue to do so. I cannot imagine it any other way. That is the Malaysia I know, love and fight to make real.

That contrast enriches, broadens and deepens me. Being immersed in the company of various races, I could appreciate their strengths, weaknesses, cultures, approaches, and lifestyles. I can appreciate how we make each other stronger and better together. I have no sense of fear or intimidation about them. Partly because of that, I do not identify with a specific race. I consider myself race-less or so mixed that my race is not discernible.

Instead, I consider myself a Malaysian.

Not a ‘Malay Malaysian’. Not Malay/Chinese.

Just Malaysian.

The government authorities, however, deem and box me as a Malay.

It cannot deal with mongrels like me. Our domestic government and private company forms have no box to tick for us. You never see a box for Malay/Chinese or Malay/Indian or Chinese/Indian. You are Malay, Chinese, Indian, or Dan Lain-Lain (And Others). Conveniently but wholly inaccurately defined. Those are forms created to reflect a crude political reality instead of our nuanced true identities: mad.

I also find it amusing that I am deemed Malay even though, by my count, I only meet two out of four of those conditions: Malaysian Parent and Religion.

I don’t have Language. Although I speak and read Malay regularly, I do not do so habitually, i.e., having an unconscious natural preference. I speak Malay with my staff, in the subordinate courts, some family and clients, but I do so deliberately. It is a conscious choice. Otherwise, it is English at home, in my office, with my friends, family (both sides of mine), and clients.

I do not conform to Malay customs. There is little about how my lifestyle, attitude, and way of thinking are influenced by it. The only portions of influence are marriage rites, respect for elders and religious obligation. What is more, I lack Malay traits like dengki, kecil hati, amok, racism, a sense of entitlement and a feudal mindset. I am generally egalitarian and democratic in outlook. I am not superstitious. I demand proof of the supernatural. I am not fixated on securing my place in heaven. Que sera sera.

I suspect these two conditions are what not just the urban and city-dwelling Malays fail but the modern Malay. There is little about modern life, diet, and opportunity in the daily life of a Malay that conforms to Malay customs, especially those envisaged in 1957.

For example, online shopping, hanging out at shopping malls, fancy wedding dinners at glamorous venues, social media fetishes, binge-watching shows, Booba tea, branded coffee, and women’s empowerment do not conform to Malay customs. They are inconsistent with the underlying culture that gave rise to those customs.

Global influences, specifically Western and Arabic culture, have so infiltrated Malay daily life and culture that it has nearly eradicated the basis on which those Malay customs were formed. The widespread domestic adoption of Arab culture, including dress, culture and language, differs from and is not Malay customs. We have more Malays who laud Arab culture instead of Malay culture.

Does indulging in these things regularly up to the point it replaces the practice of Malay customs disentitle us from being Malay? Who practices Malay customs or has a traditional Malay cultural life unassaulted by the technologies of modernity? How many of them are there?

Where do I, and those like me, sit on the constitutional front? Does two out of four count? That’s 50%. Does that make me half-Malay? Can we be a lesser or more of a Malay? Not according to the FC’s definition of ‘Malay’. The word ‘and’ in the phrase suggests the conditions are conjunctive. It can be inferred that all four conditions must be simultaneously met to be a Malay.

But two conditions that first appear clear, upon closer consideration, appear less certain.

Take Language. How much evidence do you need to determine whether a person habitually speaks? What kind of Malay? Is it the official Bahasa Malaysia, or does speaking a state Malay dialect suffice? How is the element of ‘habitually’ determined? Does habitually include proficiency? If so, to what degree?

Take customs. What Malay customs are we dealing with? Negeri Sembilan? Kelantan? Johor? Selangor? Is there a national Malay custom? The Malays came from various parts of what is now known as Indonesia. The Javanese, Acehneses, Bugis, Minangkabau, Riau, Jambi, and many others came over and made up the Malay populace. Can these customs evolve and change to something different?

Those two conditions are interesting because they are most open to evolution and change. Language lives, accumulating more words and nuances of meaning as it evolves. Malay customs evolve, too, influenced by larger cultural trends and exposure to other cultures.

That raises several questions: Do we evaluate Language and Malay customs as of 1957 or at the time when they became a matter for consideration? How much Malay customs must be conformed to before we can be said to conform to it? Can Malay customs be mixed or practised together with other customs, say, Arab culture? If so, how much blending can it take with other customs before it ceases to be a Malay custom? Can the criteria for what amounts to Malay customs change or develop?

These questions are important because they determine whether one is a Malay or if being a Malay is important.

I am grateful that I am not personally concerned about it.

For me, it suffices that I am Malaysian.

And more importantly, a Just Malaysian.

Related Posts

- The Piece of Art known as ‘The Malaysian Bar'

'The Malaysian Bar' resides on the 4th floor of the Wisma Badan Peguam Malaysia, 2,…

- The Use and Uselessness of Statutory Declarations

On 1.11.2022, Vibes.com reported the following: Despite denials by party president Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid…

- Preparing Statements of Agreed Facts and Statements of Issues to be Tried

In the preparation of trials, the court orders parties, as a matter of course, to…

- Part A, B and C of the Court Common Bundles for Trial

In preparation for the court, the lawyers for the respective parties will agree upon a…

- Analysis of Pleadings

As a litigator in Malaysia, if there is one trait we must possess, it is…

2 thoughts on “A Malaysian Mongrel”

The questions you’ve raised here have long fascinated me too, as I searched my own identity.

At the micro/individual level, my legal, political, racial, and religious identities could be seen as privileged to many in the Malaysian context, but perhaps not so much if considered in the global/regional contexts or in terms of my gender identity. This might make me a mongrel, but what’s most important to me is who I am physically, spiritually and morally – as a human.

At the macro/societal/national level, I think the legal definitions of “Malay” and “natives of Sabah and Sarawak” (not “Bumiputera”, which is purely political) are useful so far as to interpret and regulate the exercise of the limited privileges and affirmative action policies that the constitution protects following historical agreements, colonial classifications, and conditions of independence. In the heterogeneous, socially integrated Malaysia today, it is just impossible for any objective definition to do justice to how each of us subjectively define and manifest our own identities based on our personal influences. No one could ever be “biologically” or “purely” of one racial (Malay, Chinese, Indian etc) or ethnic identity (Javanese, Hokkien, Tamil etc). So on this point, I don’t think the question is necessarily whether the legal definition of Malay should be reviewed to keep up with the times, but whether the colonial legacy embodied in these constitutional provisions and classifications remain relevant and how much should it continue to be protected after 67 years.

The French in days of fur trapping Canada called the children of mixed European and indigenous parentage Metis or ‘mixed’. I think the same idea can be applied in Malaysia only I think the term of significance would be Petis since it forms an important component of Rojak Petis. Rojak Petis itself is symbolic of what the country can be: the perfect mix of fruits and vegetables bound together by Petis.