Note: This was a talk I delivered for a client that invited us to give a topic of our choice. The full talk was titled ‘How to create a paper trail and be a witness.’ I dealt with the latter topic and my colleague dealt with the former. The talk is for those that have never been a witness before.

What is a witness?

The Cambridge Dictionary defines a witness as, a person who sees an event, happening, especially a crime or accident.

In law, it is a person who saw, heard, tasted, smelled, felt or thought something that is important for the narrative of a case in court. They are there to confirm what they perceived through their senses or went through their mind.

It is useful to draw a distinction between fact and evidence.

The Evidence Act 1950 (‘EA50’) defines fact as ‘any thing, state of things or relation of things capable of being perceived by the sense…’ So if you did not perceive it through your senses, it is not going to count as evidence. And it is very likely to be a fantasy i.e., your fantasy.

A fact is what happened.

Evidence is proof of a fact.

There are only two kinds of evidence: oral evidence and documentary evidence. A witness can give both. I will discuss oral evidence first then documentary evidence.

When a witness testifies about facts (for example, whey saw or heard), what the witness said is the evidence, more specifically, oral evidence. EA50 defines oral evidence as ‘all statements which the court permits or requires to be made before it by witnesses in relation to matters of fact under inquiry:’

An easier but inaccurate way to think about it is ‘Whatever he said he saw, heard, smelled, etc.’

The statutory definition says ‘all statements which the court permits or requires to be made before it …’ That means a witness cannot simply speak about anything. He can only speak what the court allows.

So, it is important to appreciate that there are limits to what a witness can say in court. As mentioned, a witness can only give evidence of fact i.e. what he saw, heard, etc. Two implications arise from this.

Firstly, a witness cannot give their opinion. They cannot give their opinion. They are only to speak about what they perceived through their senses and what they thought at the time. That is all.

Only the court is entitled to have an opinion about the facts. And the only person that can give an opinion in court is an expert witness. Even then a court is not bound by it. A witness is not called to speak about what ifs and maybes, only what happened.

Secondly, a witness is only allowed to speak about relevant facts. Those are facts that relate to the dispute and either prove or disprove those factual disputes. So if the court case relates to a car accident claim, what underwear the bystander witness was wearing at the time of the accident is irrelevant and will not be allowed. How each driver drove is relevant because it necessary to determine who was at fault.

This is contained in section 5 EA50 which provides, Evidence may be given in any suit or proceeding of the existence or non-existence of every fact in issue and of such other facts are hereinafter declared to be relevant, and of no others.

A witness can also give evidence through contracts, letters, memos, e-mails, etc. Such evidence is called documentary evidence. EA50 defines documentary evidence very widely. It includes anything on which symbols can be recorded. So a compact disc is documentary evidence. An audio recording is documentary evidence.

An example to illustrate: X testifies in court that he saw Y go into a building. That Y went into a building is a fact. X’s testimony in court is the evidence to support that fact. X may also say that he has a picture of that; that picture is also evidence of Y going into a building.

A fact can be supported by several pieces of evidence. The more evidence that can go to support a fact, the more credible that fact is.

In summary, a witness is someone who testifies to what he saw, heard, felt, tasted, smelled or thought. He cannot give his opinion about what happened. He can only talk about what happened from his point of view and nothing else.

The Role of a Witness

The role of a witness is to give truthful evidence about what he saw or heard irrespective of which litigant calls him.

An example. You are called as a witness for the Plaintiff. However, your evidence is generally helpful to the Plaintiff but there are some portions that are unhelpful. When you are called to court, you must give the helpful and unhelpful portions. Just because you are called by the Plaintiff, it does not mean you tell a story supportive of the Plaintiff’s case or weaken the evidence against the Plaintiff.

As a witness, whether the evidence you gave is good or bad to the Plaintiff is not your problem. You have to tell it like it was, good and bad. A witness’s duty is to tell the truth in court. Your role as a witness is simple: tell the truth about what happened in relation to you.

The purpose of giving truthful evidence is so the court can make a decision based on facts, not fantasy. It is of great importance to give truthful evidence because the judge was not there when the dispute took place. She does not know anything about the dispute other than through the witness, litigant, and lawyers. She does not know (and is not supposed to know) any of those that appear before her to keep the appearance of impartiality and independence.

That means she does not know who is competent and credible and who isn’t. The only way she can get discover some sense of it is to sift through the evidence. Anyway, a judge should be entitled to have only the competent and credible before her so she can focus on resolving the irreconcilable dispute between the litigants according to the law.

That is why it is a witness’s duty to be truthful (credible) and severe punishment meets those that fail in that duty. [And that is why only competent lawyers should appear before judges, so they do not waste the court’s time.]

Just because you are called by Plaintiff, does not mean Defendant cannot interview you before the trial. There is ‘no property’ in a witness i.e., they are not on either party’s side. Or that’s the theory of it.

Witnesses that lie do so to the court as surely as they do to the opposing lawyer and her client. Lying in court is a criminal offence under section 199 of the Penal Code punishable with seven years imprisonment and/or a fine.

Although the court does not tolerate lies by a witness, it is entirely aware of human frailties. So even if the witness lies, it does not mean that the entirety of his evidence is to be rejected. This was what the Federal Court said previously:

“The first question that we have to satisfy ourselves is whether the learned judge has erred in considering the issue of credibility of witnesses in this case. Before considering the credibility of witnesses, that is Dato Mohd Said, Dato’ Amir Junus, ACP Mazlan, DSP Aziz, SAC Musa, Azizan and Ummi, all of whom were attacked by the defence, he sets out the tests to be followed at p.293:

“The Privy Council has stated that the real tests for either accepting or rejecting the evidence of a witness are how consistent the story it with itself, how it stands the test of cross-examination, and how far it fits in with the rest of the evidence and the circumstances of the case (see Bhojraj v. Sitaram AIR [1936] PC 60). It must, however, be observed that being unshaken in cross-examination is not per se an all sufficient acid test of credibility. The inherent probability of a fact in issue must be the prime consideration (see Muniandy & Ors v. PP [1966] 1 LNS 110; [1966] 1 MLJ 257. It has been held that if a witness demonstrably tells lies, his evidence must be looked upon suspicion and treated with caution, but to say that it should entirely rejected would be to go too far (see Khoon Chye Hin v. PP [1961] 1 LNS 41; [1961] MLJ 105b). It has also been held that discrepancies and contradictions there will always be in a case. In considering them, what the court has to decide is whether they are of such a nature as to discredit the witness entirely and render the whole of his evidence worthless and untrustworthy (see De Silva v. PP [1964] 1 LNS 32; [1964] MLJ 81).”

Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim v PP [2004] 3 CLJ 737

So if you are a little inaccurate, a little forgetful, and there are minor contradictions in your evidence, that will be forgiven by the court, because it is expected.

So if you truly don’t remember, say so. But it is important to appreciate that you are likely to lose credibility if you say I don’t know often, especially in relation to matters that specifically relate to you. The more you say you don’t remember things you were called a witness for, the more it raises doubts with the judge about whether you were accurate about what you claim to remember.

How to Prepare as a Witness

As a witness, you are likely to be called up by the litigant or his lawyer. Many have the naive idea that a witness simply turns up in court and speaks what he knows. That is not the case.

First, take an interest in the case. Understand what the dispute is about generally and what your role in it is Ask basic questions like:

- What is the case about?

- Which side are you asked to be a witness for?

- Which part of their case are you required for?

- What are you supposed to give evidence about?

- What is the other side saying about the evidence you are giving?

- Are there documents involved? If so, get copies of it, if you don’t already have it.

Second, once you are confirmed as a witness, you should immediately take steps to prepare a chronology of events and evidence (‘CEE’). Immediately, because the longer you wait, the less you remember accurately. Set some time aside, thirty minutes to an hour, to sit down daily to produce and refine the CEE.

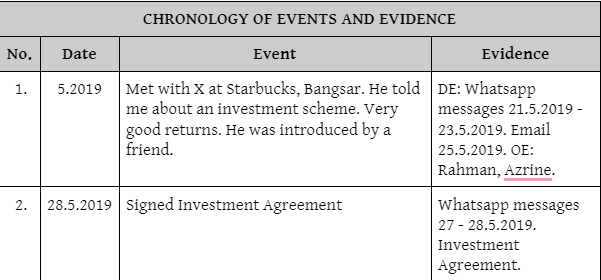

The CEE is a table of four columns. Starting from the far left, the first column is the numbering of events. The second column is the date or period of the event. The third column is a description of the event itself. The fourth column contains a reference to the evidence supporting the event and should be supported by a copy of the document where possible. An example of what that would look like is presented below.

DE: Direct Evidence | OE: Oral Evidence

For the date, get it as accurately as you can. If you cannot, month and year will do.

For the event/period, write down as much of that moment as you can remember (relating to the case, always). We want important and significant points of the narrative set down.

For the evidence, find as much as you can to support what you said, either by way of oral or documentary evidence. If possible, each event/period should be supported by evidence. Make sure to read or know about the documents that you are referring to.

Work on the CEE until you have exhausted your recollection and source of documents. Once exhausted, go through it one last time to correct any errors. After that, bind the whole thing: CEE on top, relevant documents below. Paginate the whole thing. Physical or digital. Just put it together. That CEE bundle is all you need to master.

This exercise helps you refresh your memory about the event and ensure it stays fresh. It helps you feel confident about the facts and documents especially when you are tested on them in court. It also delineates very clearly what is not within your knowledge.

It also helps inform the litigant calling you as a witness to prepare their case. This is relevant because the litigant who is asking you to be his witness will likely have his lawyer call you to prepare a witness statement for use at trial. Preparing a CEE bundle is helpful to a lawyer because it gets them into the facts and evidence immediately.

Fourth, a brief description of witness statements.

Before that, you need to appreciate that there are three phases to the examination of a witness. The examination-in-chief. The litigant’s lawyer who calls you as a witness asks you questions. The cross-examination. Their opposing litigant’s lawyer asks you questions. He will seek to undermine your accuracy or your credibility. Finally, re-examination. The litigant’s lawyer has an opportunity to explain any inconsistency raised during the cross-examination.

The witness statement takes the place of the examination-in-chief. When you get on the stand you will declare that those are your answers to the question posed to you and that they are true and accurate.

As much as possible, the witness statement should be in your own words in a language you are comfortable with. It should sound like how you would speak or write. You will find the process leceh and tedious. But it is important. You cannot sound different from your witness statement. It will show those were not your words and weaken the credibility of your evidence. Or so the theory goes.

There was once I encountered a witness statement where the witness used ‘saya’ to refer to himself. But in court, he used ‘aku’ instead. I pointed that out and he admitted that the litigant’s lawyer had ‘improved’ his language. In doing so he exposed the lawyer to a potential charge of evidence tampering.

Finally, housekeeping and mundane matters.

Make sure you put the court date, time and place down in your diary, schedule or calendar. Clear the day. Don’t fix anything else. Make sure you are there when you have to be. Do not take it lightly. If you have been served with a subpoena, your failure to attend may result in a warrant of arrest being issued against you and potential contempt charges once brought to court.

Prior to the trial, the lawyer should provide you with a copy of the court bundle of documents and your witness statement filed with the court. You should familiarise yourself with the court bundle as well as the witness statement. You are likely to be referred to both during the cross-examination. It will make it go smoother and quicker if you are familiar with both of them.

If you are not sure about where the court is or haven’t received your court documents, call the lawyer or his assistant for help.

Day of Trial

You should dress in smart casual, formal or traditional formal wear. For men, a collared shirt and long pants at the minimum. For women, modest clothing and below-the-knee skirts or dresses. Bring your Identity Card.

Make sure you get to court early. When you arrive, notify the lawyer calling you as a witness. Do not.

You will be placed in a witness room because you are not meant to hear the evidence of other witnesses. That is to ensure that your recollection is not influenced by theirs. That is why you are also prohibited from discussing your evidence with others before you are called as a witness. Ensure your phone is fully charged so you are not short of entertainment. Don’t discuss evidence during the break.

You cannot bring any notes or documents other than the witness statement to the witness stand.

In the Witness Box

What follows are things to bear in mind while giving evidence:

- Speak clearly. Take your time. There is no need to rush.

- Address your answer to the Judge, not the lawyer, even though he is asking.

- Wait to be asked the question. Don’t assume it.

- You don’t want to give out more than what is required. If they ask you about A, just speak about A. Don’t talk about B,C D, unless you must. And 19 times out of 20, you don’t have to.

- Use words. Don’t use body language like a nod or grunt. Speak clearly into the microphone so your answers are recorded by the court transcript recording system.

- If you don’t understand the question, say so.

- If you don’t know the answer, then you don’t know. Don’t invent.

- You are not there to save a situation or maintain a fiction. You are there to tell the truth.

- Use proper language. No foul words.

- Don’t write anything down. The opposing lawyer can request to see it.

- Remain calm, even during difficult questions. Remember, this moment shall pass.

- Do not get into an argument with the lawyer, even if provoked or insulted.

- Do not leave until the court gives permission.

- Leave it to the lawyer who called you to deal with the objections.

- Always remember your job as a witness is simply to state what happened. You are not there to persuade anybody that you are right.

- Do not ask questions back. Just answer the question. Avoid sarcasm.

- If you made a mistake about your previous answer, mention it to the court as soon as you become aware and tell the court what the correct answer should be.

Related Posts

- The Secret to Extrinsic Success

Extrinsic success is the acclaim, awards and accolades society bestows on us. Or discretely purchase,…

- The Death Penalty

Are you for or against the death penalty? I have never liked that question because…

- Crafting Call to the Bar Speeches | Call Speech Series

I have moved pupils' calls to the bar since 2006, which was when I crossed…

- A Klang Valley Lawyer Outside the Klang Valley

I was a member of the Kuala Lumpur Bar from 1999 until 2008 when my…

- Adducing Evidence after Trial

In a civil or criminal case, all the evidence in support of a civil claim,…